In April 2023, the Indian Parliament passed the Competition Amendment Act, 2023 (“Amendment Act”), to amend the Competition Act, 2002 (“Competition Act”).(2) The Amendment Act has introduced sweeping changes to the substantive and procedural framework of the competition law regime in India. One of the most significant amendments is the introduction of two new tools in the enforcement kit of the Competition Commission of India (“CCI”) – settlements and commitments.(3) These mechanisms are intended to enable timely intervention, to the benefit of consumers and the economy at large, as well as significantly reduce administrative costs.(4) Similar tools are already in place in several other jurisdictions such as the European Union (“EU”), United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, and Singapore.

The European Commission (“EC”) has the power to accept settlements(5) (for cartel conduct) and commitments (for non-cartel conduct) from parties under investigation. The commitments mechanism has in fact, been exercised very frequently by the EC, with a total of 43 decisions by 2022.(6) Between 2005 and 2019, more than 50 percent of enforcement decisions were taken under the commitments route, with no finding of contravention by the parties under investigation.(7) Recently, the EC accepted commitments from Amazon and closed its investigations into certain alleged anti-competitive practices in the e-commerce market.(8) It also routinely benefits from the administrative efficiencies derived from the settlement procedures; 13 out of 18 cartel cases since 2018 involved all or some parties seeking to settle with the EC in exchange for a 10 percent reduction in their fine. The EC also employs an informal “cooperation procedure” for non-cartel conduct, where there is a finding of infringement along with imposition of structural remedies and the parties are rewarded with as much as 30 percent reduction in fines for their cooperation.(9)

National authorities in Europe have also heavily relied on these mechanisms for antitrust enforcement.(10) In February 2022, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (“CMA”) accepted commitments from Google in relation to the Privacy Sandbox for its Chrome browser. In a separate investigation, the CMA is currently evaluating commitments offered by Google in relation to its Play Store billing policies.(11) The German competition law regulator, Bundeskartellamt, also recently accepted commitments offered by the German Olympic Sports Confederation and International Olympic Committee in respect of advertising restrictions imposed on the participants in the Olympic games and companies.(12)

The CCI will now therefore have a toolkit which is at par with global competition law authorities. Given the increasing focus on regulation in digital markets, such powers may help the CCI in quickly addressing potential anti-competitive conduct, while also freeing up its resources to regulate hard-core anti-competitive conduct. It however, remains to be seen how these mechanisms will be implemented in the regulations and in practice, whether they can help CCI ensure effective enforcement against competition law violations in India.

Provisions under the Amendment Act

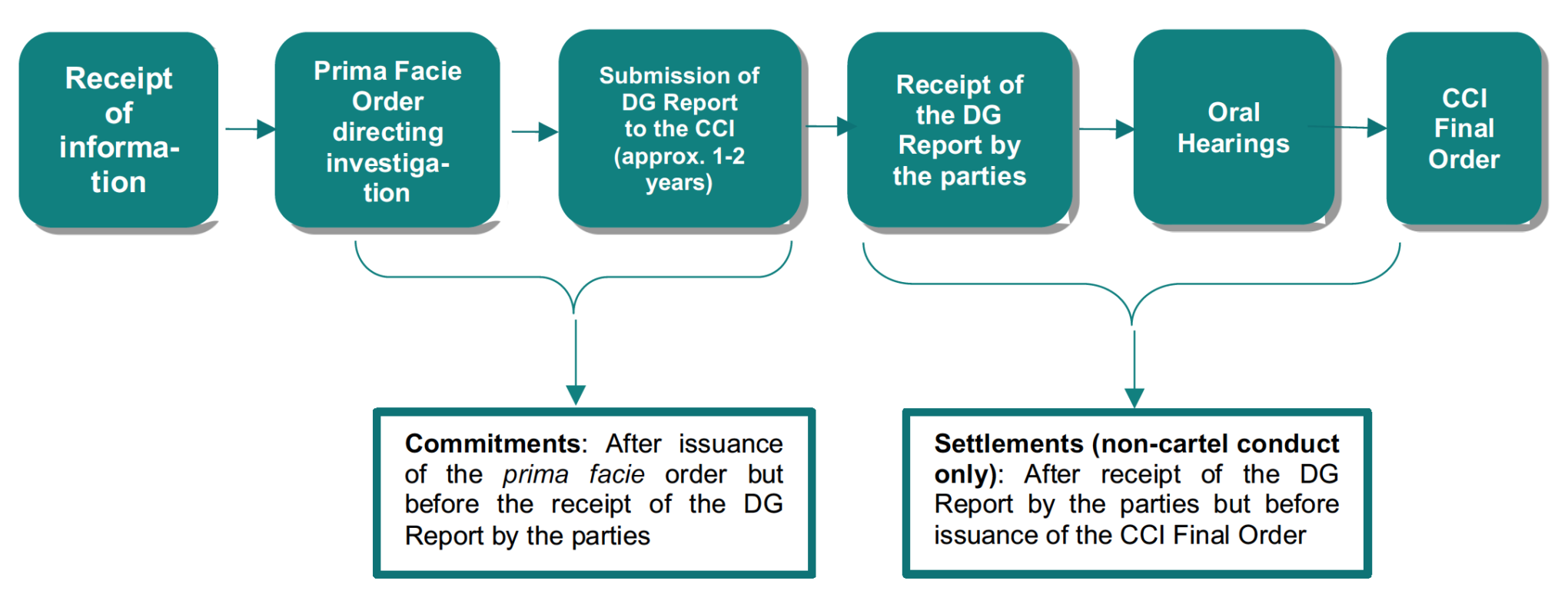

Under India’s competition law regime, the CCI, on being prima facie satisfied of the existence of a violation, can direct the Office of the Director General (“DG Office”) to initiate an investigation into the matter.(13) The DG Office thereafter submits a report on its findings after completing the investigation (“DG Report”).(14) The parties are given an opportunity to review the DG Report and make their submissions to the CCI, before a final order is issued by the CCI.

The Amendment Act introduces two new provisions, Section 48A and Section 48B, that will allow parties to submit to the CCI (subject to payment of fees) an application for entering into settlements or commitments. Under the Amendment Act, commitments may be offered at any time after the CCI initiates an investigation against a party but before the DG Report is received.(15) Settlements, on the other hand, may be offered by parties only after having received the DG Report, but before final adjudication by the CCI.(16)

The CCI would consider the nature, gravity and impact of the contraventions while assessing a proposal for settlement or commitments.(17) In case of commitments, the CCI would also consider the effectiveness of the proposal in addressing the alleged contraventions being inquired.(18) Other terms and conditions for implementation and monitoring of the settlement or commitments can also be imposed.(19) Further, the CCI is bound to provide an opportunity to the party under investigation, the DG Office, or any other party, to submit their objections and suggestions to the proposed settlement or commitments.(20) The order accepting the proposed settlement or commitments would be final, with no provision to file a statutory appeal before the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal or the Supreme Court of India.(21) If the CCI does not find the proposal for settlement or commitments to be appropriate, and the party under investigation by the CCI fails to reach an agreement on the terms of the proposal with the CCI, the CCI may reject the proposal and proceed to adjudicate on the matter in accordance with the established procedure.

The CCI would consider the nature, gravity and impact of the contraventions while assessing a proposal for settlement or commitments.(17) In case of commitments, the CCI would also consider the effectiveness of the proposal in addressing the alleged contraventions being inquired.(18) Other terms and conditions for implementation and monitoring of the settlement or commitments can also be imposed.(19) Further, the CCI is bound to provide an opportunity to the party under investigation, the DG Office, or any other party, to submit their objections and suggestions to the proposed settlement or commitments.(20) The order accepting the proposed settlement or commitments would be final, with no provision to file a statutory appeal before the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal or the Supreme Court of India.(21) If the CCI does not find the proposal for settlement or commitments to be appropriate, and the party under investigation by the CCI fails to reach an agreement on the terms of the proposal with the CCI, the CCI may reject the proposal and proceed to adjudicate on the matter in accordance with the established procedure.

Several aspects of these mechanisms remain unclear as of now, such as the nature and objective of the settlement procedures, how the guilt of parties is to be established, the factors to be considered while assessing proposals, the role of third parties, etc.

Not So “Settled” Yet: A Review of the Finer Details

(a) Timelines and Procedure

(b) Role of Third Parties in Commitments – Market Testing of Remedies

(c) Considerations for Assessing Proposals for Commitments

(d) Nature of the Settlements Mechanism and Admission of Liability

Carrot and Stick: Restoring the CCI’s Penalty Powers for Effective Adoption of the Mechanisms

In most jurisdictions,(38) the quantum of fines that can be imposed on the contravening party is 10 percent of the overall global/total turnover of the party. In India, the power of the CCI to decide the quantum of penalty was heavily diluted by the Supreme Court of India (the highest court of law in India) in Excel Crop.(39) Section 27(b) of the Competition Act empowered the CCI to impose a penalty not more than 10 percent of the average of the “turnover” for the last three preceding financial years. In line with global jurisprudence, the CCI had interpreted “turnover” to mean the “total turnover” of the party i.e. its global turnover. However, in Excel Crop, the Supreme Court held that the quantum of penalty has to be restricted to not more than 10 percent of the “relevant turnover” of the erring enterprise on grounds of proportionality to the violation. The “relevant turnover” had been defined as the turnover pertaining to the products or services (and the geography) for which the anti-competitive conduct of the parties relates to.(40) This severely reduced the scope of penalty that would be imposed by the CCI and also impacted the intended deterrent effect that such penalties should have had in the market.(41)

The 2023 Amendment Act has “re-stored” the CCI’s powers to impose penalties calculated on the basis of a party’s global turnover. This was critical to increase the attractiveness of the non-adjudicatory mechanisms for parties. In other jurisdictions as well, an introduction of cooperation or lenient regimes was coupled with increase in the level of fines. For instance, in the US, leniency was introduced in 1978, and made more generous in 1993 and 2004, whereas Congress raised the maximum jail term for antitrust offences and the maximum fines for corporations during the same time.(42) The EC adopted its first Leniency Notice in 1996 and its first Fining Guidelines, which reflected an increase in the level of fines, in early 1998. The EU Member States followed a similar pattern for example, in France, a leniency programme was introduced in 2001 and the same legislation also increased the maximum fine.(43) Therefore, it may be argued that the existence of such policies allows antitrust offenders to reduce their exposure to penalties by cooperating with the authorities. Their failure to take advantage of the cooperation mechanisms increases their culpability and should beget higher fines or penalties.

The increased penal powers of the CCI are therefore, a welcome change that would not just increase the deterrence effect against competition law violations but also act as a catalyst for the adoption of the settlement and commitment mechanisms.

Rewarding companies for cooperation with the CCI is also not a new feature in the Competition Act. The “Leniency Regime” of the CCI incentivizes companies participating in a cartel to blow the whistle for a reduction in the fine imposed by the CCI. A party that first approaches or provides vital disclosures to the CCI may receive full immunity (i.e. a 100 percent reduction) from fines.(44) The incentive of lenient treatment to a whistle blower destabilizes cartels and also ensures that the CCI does not waste its scarce resources in uncovering evidence and proving the existence of cartels.

Enforcement against cartels through the Leniency Regime has been largely successful. Since its introduction in 2017, the CCI has decided 16 cases under the Leniency Regime and there are several more under investigation. However, while the leniency mechanism may be relied upon for enforcement against cartels, it is worth assessing whether the settlements and commitments mechanisms should be limited as enforcement tools primarily for non-cartel conduct. A scenario involving non-cartel conduct is markedly different as such conduct is undertaken publicly; the difficulty in investigation of such conduct is to evaluate if the evidence is strong enough to prove the case such that the findings can withstand the test of appeals.

Conclusion

The settlements and commitments mechanisms are much needed tools to aid antitrust enforcement in India. They will offer procedural efficiency and allow the CCI to intervene swiftly and effectively in certain cases where parties are willing to close investigations sooner. Major competition authorities around the world are frequently relying on such mechanisms to achieve their enforcement objectives.

Several aspects need to, however be addressed in order to ensure that the CCI is able to effectively implement these mechanisms in India. It remains to be seen how CCI frames the supporting regulations and the clarity they bring to the operation of the settlement and commitment procedures in practice.

Endnotes

Authors: Sonam Mathur, Partner, Shubhang Joshi, Managing Associate and Riya Shah, Associate.

By browsing this website you agree that you are, of your own accord, seeking further information regarding TT&A. No part of this website should be construed as an advertisement of or solicitation for our professional services. No information provided on this shall be construed as legal advice.

Agree Disagree